We are used to the idea that the poor behave in a certain way- living for the day, devil may care, fatalistic, impulsive, enjoying life while they can- whilst the rich are more future-oriented, self-controlled and cautious. Just read the novels of Zola, for example, for vivid descriptions the appeal of present consumption over savings amongst those with the poorest lot in society.

There’s actually a lot of evidence that, statistically, this is more than just a myth. People of lower socioeconomic status-in Britain for example-do tend to discount the future more heavily, are less health-conscious and future oriented. This can lead to a particular discourse about poverty: that people’s poverty is the consequence of their impulsive behaviours, and hence that poverty is in some sense the poor’s fault or failings that leads to their being poor (there would be no other good reason to be poor, right?).

In a n ew paper coming out in the journal Behavioral and Brain Sciences, Gillian presents a different analysis of this phenomenon. What if the relative present-orientation that often goes with poverty were not a failing or weakness (or some kind of primordial character trait), but a sensible response to certain kinds of structural conditions?

ew paper coming out in the journal Behavioral and Brain Sciences, Gillian presents a different analysis of this phenomenon. What if the relative present-orientation that often goes with poverty were not a failing or weakness (or some kind of primordial character trait), but a sensible response to certain kinds of structural conditions?

Imagine a world where you felt that regardless of what efforts you made, you would be likely to be killed or lose everything at a relatively young age. What would you do? Would it make you all the more careful to eat your kale, have your testicular cancer screening and often check the pressure in your car tyres? Probably not. You would probably quite sensibly conclude that there was not much payoff to doing those things since something else would probably get you long before the benefits of those tedious efforts could be realised. You’d try to enjoy the life you could have while you had it. Thus, your present-orientedness, would be an appropriate response to the conditions under which you had to live.

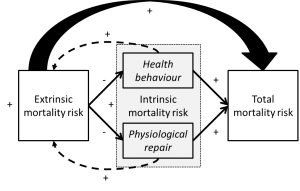

That, in essence, is Gillian’s argument. People of lower socioeconomic position in contemporary societies tend to be exposed to worlds where they are in less of a position to realise the returns on future-oriented investments, because more uncontrollable bad shocks happen to them than happen to the rich (and, with growing inequality, a more conditional benefits system, and increased economic precariousness, this is tending to become even more true). If you accept that this is true, then much of their average behaviour, ex hypothesi, makes sense. It’s not a moral failing; you would respond that way too.

Of course, it’s not quite that simple, as a perusal of the paper will reveal. One of the big themes Gillian is interested in in the paper is the idea that the consequences of poverty become progressively embedded via feedback processes. If you start out down one lifestyle path – perhaps for a small but comprehensible reason – the alternative track becomes further and further away and the chance of reaching it, or the point of trying, less and less. This kind of embedding can even become transgenerational, as the behavioural strategies of one generation determine the starting input given to the next. But the big take-home message of the paper is that structural disadvantage is in the explanatory driving seat for the behaviour of the poor. The kinds of interventions, for example for health inequalities, that are of the greatest importance are those that address the structural disadvantages that make poor people likely (whatever they do) to have positive futures they can control and rely on.

Behavioral and Brain Sciences is a peer commentary journal, so we are bating our breaths to see what colleagues in the social as well as biological sciences make of it all. One of the issues in this area is that so many disciplines have something to say about social inequality that it is easy to end up (a) relabelling ideas that in fact already exist in other disciplines; or (b) having ideas that are actually a bit different from the received ideas, but are mis-recognised as being something rather different from what you intend them to be. Let’s hope we have steered between that particular Scylla and Charibdis.

Discover more from Daniel Nettle

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.