UK readers may be wondering why Prime Minister Rishi Sunak has called a snap General Election to be held on July4th 2024, when the law did not require him to do so for another six months, and his governing party was trailing in the opinion polls. I can now reveal the answer.

Act Now!, our book setting out a series of policies to make Britain a better, fairer, healthier place to live, was due to publish in July. Clearly, Rishi could not bear to risk the public seeing what we were proposing. Best get the election out of the way before the content becomes widely known, or you’ll all be wanting it!

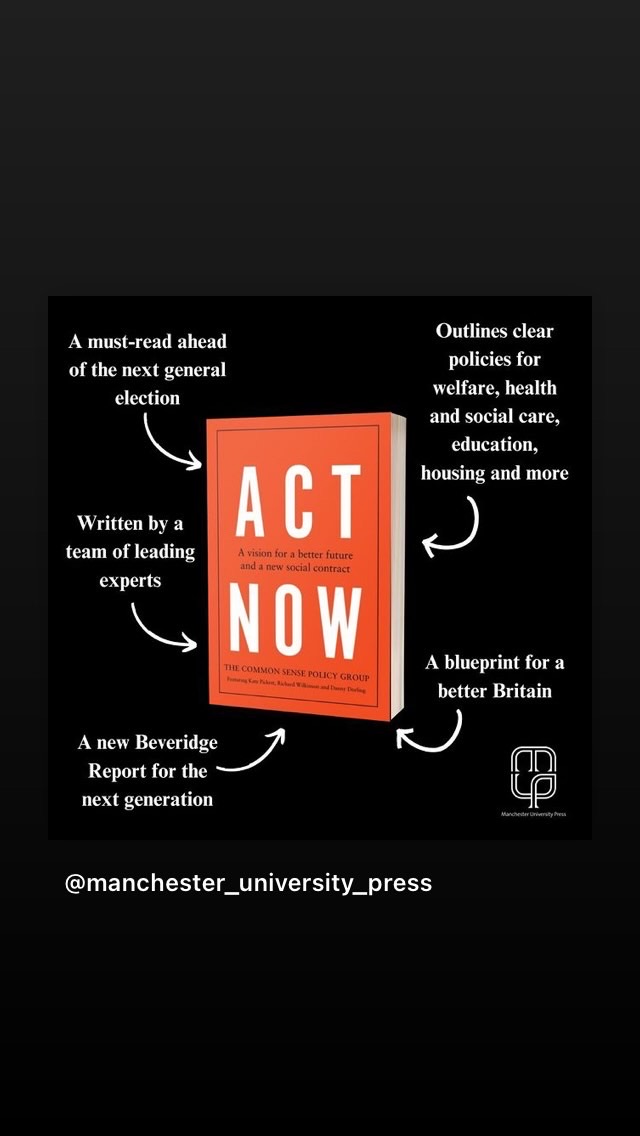

I am happy to report that Manchester University Press have worked miracles to accelerate publication. We will be launching in London on June 27 2024, and copies should be in the shops at least a week earlier (order copies here by the way). The pre-publication strapline ‘a must read ahead of the next General Election’ will still work, just.

The point of this post is to tell you a bit more about Act Now!, how it came about, and who its sinister-sounding author, the Common Sense Policy Group, really is.

The point of this post is to tell you a bit more about Act Now!, how it came about, and who its sinister-sounding author, the Common Sense Policy Group, really is.

At the end of 1930s, it was clear that the institutions of Britain needed a reboot. There had been a series of crises: the Great Depression, financial instability, populism, social unrest, and then war in Europe (sound familiar at all?). It was widely agreed that things were not working, but perhaps less easy to set out practical reforms were that would make things better; especially reforms around which people of different political stripes and traditions could come together.

It is here that the first Beveridge report of November 1942, Social Insurance and Allied Services, comes in. The first Beveridge Report is an unlikely bestseller, much of it being composed of descriptive historical and statistical information. On the other hand, Beveridge had moments of inspiring rhetoric: it is to Beveridge that we owe political nostrums like: ‘[a] revolutionary moment in the world’s history is a time for revolutions, not for patching’; and that only with a ‘comprehensive policy of social progress’ can the ‘five giants’ of Want, Disease, Ignorance, Squalor and Idleness ever be slain. Beveridge laid out in specific detail what a comprehensive policy of social progress would like for Britain in 1942. Within weeks, the report was apparently the most talked-about topic in the country, and a frequent theme in letters between serving soldiers and their families. Beveridge gave many different people a way of transforming their generalized desire for things to get better into concrete institutional forms; and hence served as a coordination point for the population’s desire for change.

Beveridge is overwhelmingly associated in people’s minds with the UK Labour government of 1945, which implemented substantial parts of the programme. However, the report influenced all the major political parties, by providing, directly to the people, a concrete plan that politicians could agree with or disagree with, at their peril, but not really ignore. Whoever had won that election would have had to implement much of it. The report was generated outside the processes of any particular political party. William Beveridge was a civil servant and an academic. He briefly became an MP, for the Liberal Party, a couple of years after the report had been published, and then, ironically, lost his seat in the 1945 election to the Labour Party that went on to implement many of his ideas.

It’s grandiose to compared one’s own work to giants like Beveridge. Nonetheless, Beveridge inspired a group of us last year, when we challenged ourselves to ask: what would ‘a comprehensive policy of social progress’ look like for Britain in 2024, rather than 1942? Though our views are politically diverse, we are broadly in agreement that Britain’s current institutions are generating: excessive poverty, inequality and hunger; a decline in the liveability of everyday civic life; needlessly poor health; insufficient sustainability; and a disengagement from the democratic progress. Diagnosis is easy, though: what is the treatment?

We set out to write a short book proposing policy measures that would help, across all the major areas of domestic governance. The author team is made up of 17 academics, politicians, and people from the voluntary sector. Although different people took the lead for different policy areas, this is a collective document, not an edited volume. That’s a challenge of course, since we didn’t all agree either substantively or stylistically (for this reason, and because he did not want his ideas to be smoothed to averageness by collaboration, Beveridge published his report under his sole name, although he had consulted many people in the course of his deliberations). We persevered, and we have produced a text that has its own voice, not a series of different voices, or the voice of any one of us.

It was an, ahem, interesting process. We were very clear we wanted each section to outline a good policy for a particular area, explain why it is good, and say how it could be brought about; nothing else. Nonetheless, the academics amongst us just couldn’t quite resist spending pages and pages diagnosing the ideological and historical origins of the current ills; and the politicians amongst us could not quite resist pen-portraiting ourselves on factory floors, in hospitals and green fields, sharing the values, shaking the hands and kissing the babies of the electorate. These are the déformations professionelles of our respective professions. But, with a lot of good-natured collaboration and a lot of last-minute hacking and editing, the text went to the publisher at the turn of 2024. The idea was for the book to launch at the houses of parliament in July, and be available over the summer when party manifestoes were being pondered ahead of an expected general election in October 2024 or so. That’s the plan that has just gone out the window.

We still hope the book will be of interest, even though the conversation it was designed to contribute to has been foreshortened. The UK is presumably about to get a Labour government, but their initial manifesto will be a slim, steady-the-ship document. What larger political settlement Labour will work towards in the years ahead is still to be determined. And, the new parliament may include more liberals and more Greens than the current one (we count the deputy leader of the Green party of England and Wales amongst our author team). There is a still a chance for the political conversation to move into new territory after the election, and hence still a chance for Act Now! to be relevant.

I won’t say much about what the Act Now! programme is. I hope you will read the book and see what you think. There are not many jokes but it costs under a tenner. What I will say is that the measures are costed and feasible: we include amongst our team the former chief economist of the Institute for Public Policy Research. Moreover, we have done a lot of opinion polling, and the proposals seem to be popular. In all our public opinion research, we find a tremendous public appetite for quite far-reaching progressive change. Don’t let the newspapers tell you the electorate is socially conservative and basically committed to the status quo; that characterisation may well describe newspaper owners, but it does not describe the electorate. People want the hope of a better society in the future than in the past.

This is my first foray into these non-academic waters (teaser, not the last: look out for another volume early in 2025). I am delighted and surprised by the enthusiasm of the reaction to Act Now! so far. I don’t kid myself that our thinking is that original or our prose that magisterial. I think it just shows that many people share the same appetite that started us off on the journey: to identify a practical progressive vision for our times.

Philip Pettit of Princeton was kind enough to describe it as: ‘a coherent, radical, and feasible manifesto for government. Given the chance, it would ignite enthusiasm, win the young back to politics, and enable people to enjoy security and freedom in their life with one another and with the powers that be. It calls us back to a realistic image of the good society.’ For Will Snell of the Fairness Foundation, this is: ‘a genuinely radical and comprehensive plan to rebuild our society, economy and democracy from the ground up….unusual in that it combines a bold overarching vision with detailed, evidence-based policy proposals, and demonstrates that they are popular with the public. The question now is whether our politicians are prepared to listen.’ Peter Jones of Newcastle University sees ‘an inspiring, imaginative and radical vision for Britain’s future, equal in ambition to the challenges the country faces.’ And David Wilson of Birmingham City University urges you to ‘read it if you want to see what real pragmatic reforms could do and use it to remind yourself that there was a time when our politics wasn’t inert, ineffective and indolent.’

Former archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams gifted us a beautiful and uplifting introduction. In his view, ‘the proposals in this book are detailed and pragmatic, set out with careful attention to how they might be implemented and how they might be funded. These chapters are not an idealistic rant demanding some sort of total recalibration of how we live. But they are unmistakeably radical, in the sense that they interrogate what the political establishment of both left and right take for granted, what they think is achievable and acceptable….[They] look towards [a] shift in the imagination – the spirit – of Britain, returning repeatedly to that fundamental challenge of how we sustain a social order that does justice to the most humane, generous and grounded instincts of our communities.’ To have our intent to be heard in this way is a thousand feet above what Matthew Johnson and I could have hoped for, on an unsuccessful walk to Benwell Nature Park, Newcastle, in the rain, back at the outset of this process.

What about our authorial name, the Common Sense Policy Group? Names containing ‘common sense’ are often found badging groups of extreme libertarians who want to undermine the state, or social conservatives whose mission is to defend traditional social hierarchies. What business does a self-identified progressive group have describing their politics as ‘common sense’?

We did this on purpose. We’d like to reclaim the notion of common sense for people who want an ever better, fairer, more humane society for ever more of the people. The political right presents progressive ideas as theoretical, abstruse, ideological, as coming from foreign intellectuals with a tenuous relation to place, tradition or practicality. They invoke common sense in opposition to this, to justify current inequalities of resources and power, and bind us into grim understandings of the limits on the what is possible. It may not be pretty, they tell you; but common sense tells you there is no alternative.

We take a different view. The present, concentrated, social-good-hostile political settlement is not the only way that human societies could or have lived. It’s not the most ‘natural’ way, nor the way that most faithfully reflects the moral and imaginative capacities of most people. It is one rather specific way of being a society, a way that was carefully constructed, justified and propagated quite recently by a small sector of the population who had enough power and saw it as in their interests to do so. The insistence that it is common sense, for example, that most of the growth of the UK economy goes to a small group of highly wealthy people, or that our rivers are full of sewage whilst our water companies pay dividends to their private owners, is an ideological move. It’s not common sense at all.

On the contrary, there is a case to be made that there exists, in humans, a common sense, or a least a commonly held set of moral sentiments, that is the wellspring of the progressive impulsive. People at all times and places have cared about the least well off in society. They have been averse to certain types of inequality and motivated by fairness. They have had the sense that social relationships and institutions, not just individual resources, are important. They are happy to contribute to public goods as long as others also do so. Undoubtedly, they value their autonomy, freedom and privacy too; these are also part of their common sense. These widely-shared human sentiments provide us with an infrastructure for imagining visions of how societies can, not just be good enough, but become ever better as material abundance increases through technical progress.

In short, the Common Sense Policy Group wants to flip the flop on the invocation of ‘common sense’ in political conversation. We don’t agree that it is strange alien ideologies that give people the idea of a better, fairer, more equal society; nor that it is common sense that provides the grim reminder that we have to tolerate and normalise the current concentration of wealth, health and power. On the contrary, the defenders of the current concentrations reflect one ideological group in one place, at one time, motivated by some highly abstract conceptions of how things should work. It’s common sense that says: time to act.

Discover more from Daniel Nettle

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.